Cinema's First Century

The rise, fall, and revival of Ann Arbor’s downtown theaters

The first movie shown in Ann Arbor was The Great Train Robbery. Filmed a century ago, in 1903, the twelve-minute adventure didn’t make it to town until the following year. On September 26, 1904, it appeared as the last item on a sold-out seven-part program at the Light Armory at Ashley and West Huron. Handcuff King Fred Gay led a bill that included minstrels, jugglers, and a boy tenor.

Films may have started as an afterthought, but they soon became a draw in their own right. One of the first movies to tell a story, The Great Train Robbery featured a long list of technical firsts, among them the first intercut scenes and the first close-up--an outlaw firing a shot right at the audience. The Ann Arbor Times-News reviewer reported that it required “no great stretch of imagination for the spectator to persuade himself that he was looking at a bit from real life.”

“The Great Train Robbery has been called the picture that launched a thousand nickelodeons,” laughs Art Stephan, president of the Ann Arbor Silent Film Society. Within three years of its showing, three nickelodeons (named for their 5¢ admission charge) popped up in Ann Arbor, along with three new vaudeville theaters whose entertainment included movies.

Ann Arbor’s wide audience, encompassing both townspeople and university students and faculty, has supported an abundance of theaters ever since. “Ann Arbor is one of the great movie towns in the country,” says Russ Collins, executive director of the Michigan Theater. These days, popular films appear almost exclusively in huge multiplexes on the edge of town. But for most of a century, Ann Arbor supported a wide array of downtown theaters, from the first nickelodeons and vaudeville houses to glorious movie palaces like the Michigan.

The Theatorium, “Ann Arbor’s Pioneer Picture Theater,” opened in November 1906 at 119 East Liberty (now, aptly, the home of Liberty Street Video). It showed three short movies for 5¢, changing the offerings three times a week.

The Theatorium wasn’t alone for long. In December the Casino opened at 339 South Main (now the Real Seafood Company restaurant). It advertised that it would cater to women and children and “give good clean shows which all can patronize.” The Theatorium and the Casino were joined in 1907 by the first campus-area theater, the People’s Popular Family Theater. Soon renamed the Vaudette, it was at 220 South State, where Starbucks is now.

Opening a nickelodeon was cheap--all that was needed was an empty storefront, a projector, and some folding chairs. The entrepreneur would put up a sheet at one end, install a box in the door for selling tickets (giving new meaning to the term “box office”), and get a player piano or phonograph for background music-—and he was in business. Called “the poor man’s show” or “democracy’s theater,” nickelodeons were a craze all over the country, appealing mainly to poorer audiences. The News didn’t make much of the nickelodeons’ openings, although it ran their ads.

Also showing films were two new vaudeville theaters. The Bijou, at 209 East Washington, opened the same month as the Casino, followed by the Star, at 118 East Washington, in August 1907. Although they also charged 5¢ admission and were scarcely bigger than the nickelodeons, both had stages at one end that enabled them to present live shows as well as movies. Both received more notice in the local papers than the nickelodeons had.

Maybe protesting a little too much, the Bijou ad invited audiences to “come and see the cozy theater and enjoy strictly high class moral entertainment.” The Star has gone down in history as the site of a student riot on March 16, 1908.

According to Ann Arbor police lieutenant Mike Logghe’s True Crimes and the History of the Ann Arbor Police Department, the riot started as a student protest against manager Albert Reynolds, who allegedly had tried to win a large bet by getting a U-M football player to throw a game. When protesters failed to get Reynolds to come out (reports differ on whether he exited through the back door or was hiding in the basement), they began throwing bricks stolen from a construction site across the street. The riot lasted all night, in spite of appeals by both law dean Henry Hutchins and U-M president James Angell. Eighteen students were arrested, but charges were later dropped when they agreed to raise money for repairs.

A much larger and more impressive early theater was the Majestic, at 316 Maynard (now a city parking structure). Unlike the nickelodeons, the Majestic enjoyed detailed local press coverage of its planning and arrival. The Athens, 117 North Main, the town’s major location for live stage shows, had closed in 1904, leaving a keenly felt gap.

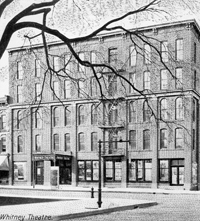

The Majestic was built by lumberyard owner Charles Sauer, who converted an indoor roller skating rink into a huge theater--1,100 seats--complete with stage, dressing rooms, balcony, box seats, ladies’ waiting room, confectionery, and manager’s office. It opened September 19, 1907, with The Girl of the Golden West, a live musical about the 1849 gold rush. The Majestic showed movies from the beginning, but vaudeville acts were its main draw--especially after 1908, when the former Athens Theater, remodeled and reopened as the Whitney, reclaimed its position as the preferred place for prime stage shows.

Of the six early theaters, the Majestic was the only one to last. By 1912 all three nickelodeons were gone--the Theatorium became a photography studio, the Casino a grocery store, and the Vaudette a shoemaker’s shop. All around the country nickelodeons were closing, Art Stephan says, mainly because the early movies weren’t very good: “They were not very exciting--just a novelty.” The small vaudeville theaters lasted a little longer, but by 1915 the Bijou was gone. The Star was renamed the Columbia, then closed for good in 1919.

Despite the nickelodeons’ failure, a few far-thinking producers kept developing and improving movies, making them longer and more sophisticated. In 1913 the Majestic announced it was switching to movies as its lead attraction. Manager Arthur Lane promised audiences “high class feature motion pictures” such as Ben Hur and Tess of the D’Urbervilles. In 1914 the Whitney also started occasionally showing movies. Seeking to lure middle-class audiences, it promised “good clean pictures that anyone would be glad to see.”

Then, in a five-year period, four new theaters specifically designed to show movies opened. The Orpheum at 336 South Main was the first, built in 1913 by clothier J. Fred Wuerth. The architect, “Mr. F. Ehley of Detroit,” designed an arched facade reminiscent of Adler and Sullivan’s 1889 Auditorium Building in Chicago (the arch now frames the entrance to Gratzi). Inside, the decor included fancy paneling and box seats. The opening performance featured The Hills of Strife, about feuding mountaineers, plus two other movies and a live show by the Musical DeWitts. It drew such a crowd that people had to be turned away.

The next year, 1914, Selby Moran built the Arcade at 715 North University, at the end of an arcade that ran along the north side of a tailor shop. Just three years later, Moran expanded the theater from twenty-six rows of seats to forty-three and added a balcony and boxes. The projector (or “motion picture machine,” as they called it then) was on the second floor--actually in the tailor shop, outside the theater proper. “We used to go to doubleheaders at the Arcade on Saturdays,” recalls John Eibler. “My mother would drop us off and take a chance when to come back. The time was doubtful when we’d come out--we had to see the whole thing.” He remembers seeing “cowboy and Indian” pictures, particularly Tom Mix features.

The Rae, at 113 West Huron, opened on September 11, 1915. At 385 seats, it was the smallest of the new theaters. Its name was an amalgam of the first initials of its three owners--Russell Dobson, Alan Stanchfield, and Emil Calman. Stanchfield, the on-site manager who eventually bought the others out, visited theaters all over Michigan and Illinois to learn the tricks of the trade. He did almost everything himself--took tickets (he knew the ages of all the kids and could charge accordingly), climbed a ladder to run the projector, and hawked refreshments up and down the aisle between reels. Bob Hall, a regular customer, recalls watching cowboy movies and serials. “Sometimes the policeman on the beat would come in and stand at the back to watch,” Hall says.

In 1918 Fred Wuerth added a second theater, naming it after himself. (He also built one with the same name in Ypsilanti.) Set perpendicular to the Orpheum, the Wuerth was reached from Main Street through a skylighted arcade to the north of the owner’s clothing store. A Hope-Jones organ was placed so it could be heard in both theaters.

One of the most important films ever, Birth of a Nation, bypassed all four of the new theaters in favor of the Whitney. D. W. Griffith’s Civil War epic was presented as if it were a live road show, traveling around the country with a twenty-piece orchestra. Admission to the four showings on May 18 and 19, 1917, was $1.50—at a time when most ticket prices were 5¢ or 10¢.

Although seriously flawed by Griffith’s racist portrayal of newly freed slaves, the film was a turning point in movie history, showing audiences how engrossing this new medium could be. “It’s hard to overstate the importance of Birth of a Nation,” says Collins. “Griffith coalesced a film language recognizable today, the technique of telling a story with film.” The following week the Whitney showed Intolerance, which Griffith produced as an answer to criticism of Birth of a Nation.

The days of releasing many prints simultaneously across the nation were still in the future: Birth of a Nation had been shown in bigger cities in 1915 and Intolerance in 1916. But movie exhibition was already becoming more organized. At first, all the early movie theaters were run by their owners. With the exception of the Rae, however, all were eventually leased to the Battle Creek–based Butterfield theater chain.

Gerald Hoag, Butterfield’s manager of the Majestic in the 1920s, faced the challenge of handling the rushes college students made on the theater, usually after a victorious football game. “They’d holler and yell and demand a free movie. They always got in,” recalls Bob Hall, who as a small boy took part in one of these rushes. “I was scared stiff--I was afraid I’d get squashed--but I wanted to see a free movie. My mother didn’t like it. She castigated me when I got home.”

Hoag, a big Wolverine fan, hired football players as ushers. In the days before regular radio sportscasts, Hoag obtained scores from the ticker-tape machine at Huston Brothers’ pool hall on State Street and announced them to his audience. Then he got a better idea: he leased a direct telegraph wire from the press box wherever the U-M was playing and had Fred Belser, a telegraph operator at Western Union, sit on stage and transcribe the messages. Hoag would read the play-by-play to the audience while an assistant moved a toy football across a mocked-up field. At halftime Hoag presented a vaudeville show.

One of Hoag’s claims to fame was discovering Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians. In 1922 Waring’s band played at the annual J-Hop at Waterman Gym. Although two more famous bands were also playing, Hoag noticed that most of the dancers drifted over to Waring. Hoag booked him at the Majestic, where he stayed six weeks, playing one-hour sets interspersed with movies. That engagement led to work in Detroit and other big cities, and for the rest of his career Waring credited Hoag with giving him his big break.

The acme and the last hurrah of the silent movie era in Ann Arbor was the opening of the Michigan Theater on January 5, 1928. The grandiose “shrine to art” reflected a national trend toward extravagant movie palaces. Starting in the teens with scrumptious theaters modeled loosely on the Paris Opera, designers segued into increasingly fanciful Egyptian, Spanish, Chinese, Mayan, and Babylonian themes. “Movies were considered low-class entertainment. The movie palaces were designed to legitimize movies as middle-class entertainment,” explains the Michigan’s Russ Collins.

The Michigan was built by Angelo Poulos, a Greek immigrant who was co-owner of the Allenel Hotel and an organizer of St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church. Although the Michigan’s style is usually referred to as “Romanesque Revival,” architect Maurice Finkel explained in a News interview that he worked in a mixture of styles--classical, medieval, Romanesque--that he thought would fit with U-M academic buildings and fraternities. (Many Ann Arborites will remember Finkel’s widow, Anya, who managed Jacobson’s hat department for years and was known for her frank advice.)

The Butterfield chain transferred Hoag to the Michigan along with most of the rest of the Majestic staff, from ticket takers to ushers. From then on the Majestic was devoted completely to movies, since the Michigan was a better place for stage shows, and the Arcade was demoted to a second-run theater.

The Michigan opened to a sellout crowd. Entertainment included an overture written for the event and a live show, The Dizzy Blondes Dance Revue. The featured movie, A Hero for a Night, was supplemented by shorts, a comedy, and a newsreel. But the Michigan was out-of-date the day it opened: the first successful talkie, The Jazz Singer, had premiered the year before.

Talking pictures came to Ann Arbor on March 21, 1929, when the Wuerth showed The Ghost Talks. While other local owners hesitated to spend money on sound systems, Fred Wuerth had figured out that after the initial investment, he could save money replacing live vaudeville acts with short one-reel films. Talkies had been around in bigger cities since The Jazz Singer, and Ann Arborites were ready: the waiting crowd lined up down Main Street and around the corner onto Liberty.

Other theaters had to add sound quickly to remain competitive. On June 16, 1929, the Michigan showed its first talkie, Weary River. The Majestic also switched to talkies that year. The Arcade, too, was scheduled for conversion, but burned down before the work could begin. (The Rae also burned the following year; at both theaters, the fire started when highly flammable nitrate film ignited, but the only injuries were minor burns to the projectionists.)

Both the Orpheum and the Whitney closed in 1929 but reopened in the mid-1930s. With no one building new theaters during the Great Depression, the rest of the lineup stayed the same. First-run movies played at either the Michigan or the Majestic, because they were the largest theaters and the ones best located to take advantage of both town and gown patrons. Second-run and B movies played the theaters downtown.

The Michigan and Majestic were the theaters to take dates to on Friday and Saturday nights. Jack Dobson remembered going to movies for 35¢ and then to Drake’s for a malted or a milk shake. Al Gallup started dating a little later; by that time, he recalls, “both the Majestic and the Michigan were forty cents.” But even with the price increase, “for a dollar you could have a date. You’d go to Drake’s after the show for a Coke.” Ted Palmer preferred the Betsy Ross restaurant in Nickels Arcade: “There were no college kids in the Betsy Ross. We’d get a lemon Coke or a cherry Coke--one Coke and two straws.”

Although not as fancy as the Michigan, the Majestic still got important films--including 1939’s Gone with the Wind. “Everyone wanted to see Gone with the Wind,” recalls Bob Steeb. “I went with my wife. We worked at Wahr’s on State Street and took the day off to see it.”

For many people who grew up in Ann Arbor, though, the fondest cinematic memories are of kids’ movies. On Saturday mornings, if they could spare the money and time, they could see full-length movies made for children at the Michigan. Or they could head for the Whitney or the Wuerth, where the movie might not be as good, but there’d also be a serial.

Serials typically consisted of six or seven weekly installments, each twenty or thirty minutes long. Episodes always stopped at a perilous moment--most famously, with the heroine about to be run over by a train. “We could hardly wait for the next Saturday,” recalls Palmer. “We’d replay the movie all the way home, shooting the bad guys.”

During World War II the bad guys were Axis soldiers. Coleman Jewett remembers watching serials such as Don Winslow of the Navy and Spy Smasher. Even the Phantom, Jewett says, added Nazi-hunting plots.

On Saturdays in the late 1940s and early 1950s, “kids would get in for ten cents,” recalls Bob Mayne, a projectionist at the Wuerth. “We’d show ten cartoons, then a serial--Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Buck Rogers--then a feature film like Gene Autry.” Once Mayne projected a Donald Duck cartoon backwards. “The kids loved it,” he remembers, “although my boss was mad.”

The Orpheum’s fare was originally very similar to the Wuerth’s, but it later established a niche playing to the more intellectual crowd with documentaries, revivals of prestigious American films, and foreign films--The Red Shoes is the movie people most often mention having seen at the Orpheum. Coleman Jewett also saw Camille and The Hunchback of Notre Dame there, while Mark Hodesh recalls going with his parents to see travelogues.

A rite of passage among kids was to sneak into the theater. At the Orpheum or Wuerth, those in the know would sometimes sneak into the other theater through a connecting tunnel. Of course any place that backed onto an alley was fair game--the kids exiting would hold the door for those who wanted to come in. Ted Heusel, who ushered at the Michigan when he was a teenager, told his friends to just pretend they were giving him a ticket. At the Majestic, some kids learned how to get in by going up the fire escape.

Once the economy recovered in the early 1940s, Butterfield considered remodeling the Majestic but instead decided to build a new theater. The Majestic closed on March 11, 1942, and the State Theater opened a week later. Not wanting to appear unpatriotic, Butterfield management emphasized that the necessary permits were issued and materials purchased before the attack on Pearl Harbor the previous December.

Six buildings along State were razed to make room for the new Art Deco theater. (The architect was C. Howard Crane, who also designed Orchestra Hall and the Fox Theater in Detroit.) The Majestic’s manager and staff all moved over to the new theater. “It was a big deal when it opened,” recalls Gallup. The premiere movie, appropriate for the times, was the Dorothy Lamour–William Holden musical The Fleet’s In, about a sailor with an inflated reputation as a lady-killer.

A highlight of Ann Arbor movie history was the 1949 premiere at the Michigan Theater of It Happens Every Spring, a baseball movie starring Ray Milland and Jean Peters. The film was based on a story written by U-M vice-president emeritus Shirley Smith, and the Ann Arbor showing actually preceded the “world premiere”—that took place in the movie’s location, St. Louis, two weeks later. A searchlight spanned the skies, the U-M Concert Band played in front of the theater, and the street was blocked off while U-M president Alexander Ruthven and Ann Arbor mayor Bill Brown presented Smith with their version of an Oscar.

The rise of television in the 1950s hit the oldest theaters first. At the Whitney, once host to such glamorous stars as Maude Adams, Katharine Cornell, and Anna Pavlova, the top balcony was closed off for safety reasons. “Four four-by-fours were holding up the whole projector. It was pretty heavy--the whole thing would shake,” recalls Bob Mayne, who once managed to sneak a look. The two lower balconies, Mayne adds, became “a necker’s paradise.” Walter Metzger recalls that the kids thought (possibly correctly) that there were bats in the top balcony, and their fears made scary movies at the Whitney even scarier.

“It was rat infested, or at least rumored to be. We told the girls that rats were running around so they’d stay close,” laughs Gallup. In 1952 the Whitney was closed by court order. The building was torn down in 1955.

The Wuerth, also, had clearly seen better days when its run ended. Carol Birch recalls the theater in the 1950s as “creepy. It was run down--people didn’t go there much. It was dark to get to your seat.” In 1957 the Wuerth and the Orpheum both closed.

To cater to the art-movie audience that had patronized the Orpheum, Butterfield built the Campus on South University. “It was a real nice one-show theater,” recalls Mayne. Lois Granberg, ticket taker at the Michigan, became manager, and most of the rest of the staff, including projectionist Mark Mayne (Bob Mayne’s father), transferred from the Orpheum. Doug Edwards, who was a projectionist at the Campus, recalls that although it was less opulent than the Michigan and the State (where he also worked), “it was the newest, most modern, with chrome and pastels and a concession stand. It was the place they’d have gimmick films, like surround sound.” During the height of the 1960s foreign-film craze, crowds lined up along South University to see the latest Fellini or Bergman work.

When a group headed by Ken Robinson and attorney Bill Conlin built the Fifth Forum in 1966, Conlin was also thinking of providing a successor to the Orpheum. “We had a contest in the Ann Arbor News to name the theater,” he recalls. The Fifth Forum’s first big success was Georgy Girl, with Lynn Redgrave. The Fifth Forum kept showing the romantic comedy for more than six months, Conlin says--in contrast to the Butterfield theaters, which were able to book movies only for short periods.

The Fifth Forum was the last commercial movie theater built downtown. The cinematic migration to Ann Arbor’s edges started the following year, when the Fox Village Theater opened on Maple Road. In 1975 the city got its first multiplex, a four-screen United Artists theater at Briarwood. Films at “the one-screen movie theaters changed every week and then were gone,” explains Patrick Murphy, a projectionist who worked in several Ann Arbor theaters at the time. “Showing four for a month was better, economically speaking.” Expanded choices and easier parking soon lured most casual moviegoers to the mall. “We would show movies at the Campus to ten or fifteen people,” recalls Edwards.

Butterfield fought back, dividing the State into a quad in 1977 with two screens downstairs and two more upstairs in what had been a balcony, but the firm was just buying time. In 1979 Butterfield quit programming at the Michigan. The theater-loving community, worried that the beautiful building would be torn down or altered for an incompatible use, mobilized to save it. The mayor at the time, Lou Belcher, personally promised that the city would buy the theater, going to council and the voters for authorization only after the fact. The daring deal paved the way for a 1982 millage that led to its restoration and operation by the nonprofit Michigan Theater Foundation.

The Briarwood multiplex expanded from four theaters to seven in 1983. The following year, Butterfield gave up the ghost, selling its remaining theaters to Kerasotes Corporation. Kerasotes kept the State but sold the Campus. “It was more valuable as real estate,” explains John Briggs, who was local president of the International Alliance of State and Theatrical Employees at the time. The Campus was torn down and replaced with a mini-mall.

Kerasotes tried to make the State profitable by replacing union projectionists with lower-paid workers. New technology could fit a whole movie on a single huge spool of film, rather than on small reels that had to be changed every twenty minutes--so one person could run four or even eight movies at a time. Union members and U-M students picketed, and in 1988 Kerasotes sold out to Hogarth Management, a real estate company owned by bookstore founders Tom and Louis Borders. Kerasotes “suffered some financial loss, but that didn’t run them out of town. The changing times with the cineplex at Briarwood is probably what did it,” says Edwards, who was one of the picketers. “The ‘GKC’ rugs are Kerasotes’s only contribution to the State,” laughs Murphy.

Hogarth leased the main floor of the State to Urban Outfitters but kept the two upstairs screens. “I was involved in the restoration of the Michigan Theater and had a soft spot for movie theaters,” says Roger Hewitt, who ran Hogarth. “I wanted to keep the movie space, and Tom and Louis were supportive.” Under Hewitt’s direction, the State’s original marquee was also restored. Hogarth initially leased the upstairs to the Spurlin family of Aloha Theaters; after the Spurlins left in 1997, the Michigan Theater was hired to do the programming and publicity. Movies that formerly would come to the Michigan for just a few days can now be transferred to the State for a longer run.

The Fifth Forum was not only the last commercial theater built downtown but also the last to close. Conlin’s group sold it to Goodrich Theaters, which renamed it the Ann Arbor Theater and divided it awkwardly between two smaller screens. It showed its last film in 1999 before being remodeled into an office building with an interesting metal facade.

Ironically, the Briarwood multiplex that devastated in-town movies was itself destroyed by the next new development. The whole United Artists chain went bankrupt three years ago under pressure for newer, even bigger movie houses--represented locally by Showcase Cinemas and Quality 16. After standing empty for several years, the Briarwood theaters reopened last year under the management of Madstone, a small chain that mixes first-run films with art movies and classics.

The venues have changed, but Ann Arbor is still a good movie town. Between them, Showcase and Quality 16 offer forty screens of first-run fare. Fox Village is now a bargain-priced fourplex specializing in second-run films. For more exotic productions, we have the Michigan, State, and Madstone. “Very few towns with a population of a hundred thousand have the choices of movies we have,” says Collins.

[Photo caption from book]: Orpheum, 326 South Main, was the first theater in town built specifically as a movie house. “Courtesy Susan Wineberg” [Photo caption from book]: In the pre-television age, area children enjoyed going to movies on Saturday afternoon at either the Michigan, Wuerth, or Whitney. “Courtesy Bentley Historical Library”

Doc

Subjects

AA Observer

Buildings

Business

Drama

Entertainment